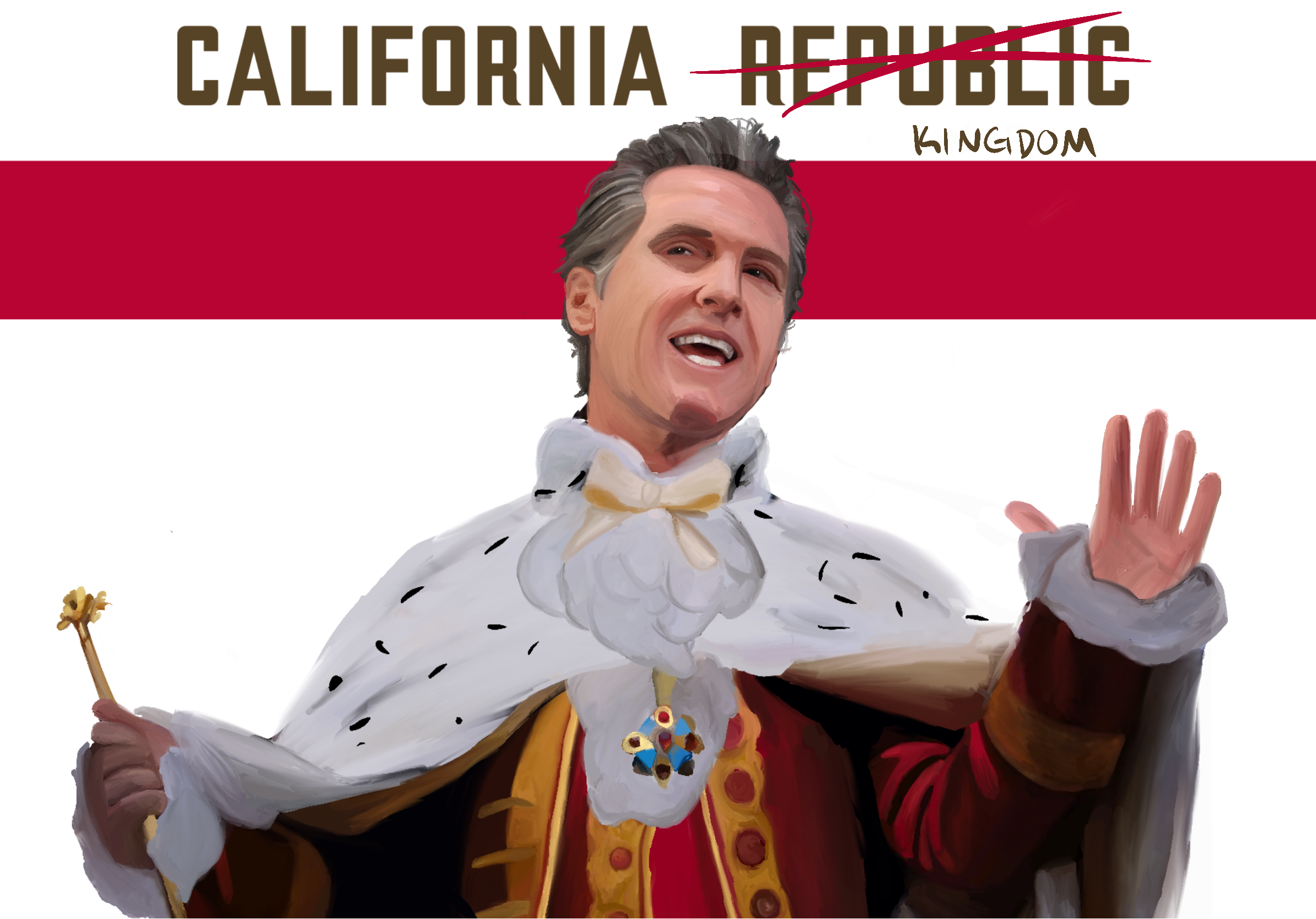

The Practicality of Big Government in California and Beyond

Graphic designed by Gil Evangelista Martinez

On Sept. 28th, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law AB 2011, greenlighting the conversion of derelict commercial spaces into housing, regardless of local government objections. The bill is the latest in a series of moves meant to tackle California’s ballooning cost of housing, limiting the power of cities and counties to micromanage or block new construction. That same day, Newsom gave his signature to AB 2097, eliminating parking mandates for developments near mass transit, and AB 2221, which specifies legal ambiguities surrounding what constitutes a ‘granny flat’, ending the ability of localities to deny their erection on arbitrary grounds.

These policies are, to a certain extent, anti-democratic, as they override local government. Mayors and city councilors, the level of government closest to the electorate, have an obligation to satisfy their voters. If these voters just so happen to desire mile after mile of red tape, what right does a far-off capital have to override the desires of their community? The purpose of government is to nurture an environment wherein individuals and communities may thrive. Should a local government instead become a tool of those who seek to deprive others of opportunity – which usually takes the form of shooting down opportunities for new families to own a home – it is right to strip local government of its powers for the sake of society at-large. California is right to assert itself over local governments in the realm of housing, and ought to extend this reach to other matters. The practical benefits of having local regulators formulate and enforce their own public policy are near zero. The state should recognize this and strip them of these powers in favor of more unitary control.

Much of California’s housing woes can be attributed to the practice of allowing land use to be decided on a municipal level by elected officials. Whenever a new development is proposed, neighborhood busybodies swarm to lobby against it, packing town halls to barrage their councilors with a cartoonish list of reasons to hobble development. In 2019, a community group successfully swayed the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to block the construction of a 63-unit apartment on the grounds it would cast a partial shadow over a nearby park for several hours a day. City officials indulge in the madness because their livelihoods depend on it; they cannot afford to anger the politically active as their elections are often won by several hundred votes.

Rendering of the failed Folsom Street Apartment Complex, courtesy of SF Planning

Such an unserious approach to policy making could be laughed off were it not so detrimental to the public’s well-being. The National Bureau of Economic Research estimates the current legal framework drives up the median Bay Area home price $410,000 higher than it would be otherwise. This should outrage more than just price-gouged mortgagors, as high housing costs are one of the best predictors of a state’s rate of homelessness. With this in mind, the state’s recent attempts to punish cities who try to weasel their way out of building new housing (the Attorney General threatened a wealthy suburb of Woodside after it tried to declare itself a mountain lion sanctuary to avoid permitting multi-family homes) should be applauded and taken a step further. Few Californians enjoy comparisons to Texas, but they should take note of how their friendly rival approaches housing. While cities of the Golden State smother new developments in mountains of legalese, Houston boasts that it lacks any form of formal zoning, and its citizenry have thrice voted against attempts to grant the city such powers. As a consequence, median home prices in Houston are a stupefying 75% lower than Los Angeles, despite comparable median incomes and geography. Should Sacramento feel brave enough to impose what is admittedly a radical change, there is little reason to suspect a similar level of affordability is not possible this side of the Rockies.

Housing is not the sole realm where the Capitol ought to assume control; policing and sentencing can be improved with a more direct hand. District Attorneys have the sole power to decide which criminal cases are brought to trial and which are dismissed, as well as the severity of the charges. The platonic ideal of a DA would be a dispassionate figure concerned only with facts, but just as city councilors must rely upon local activists to secure their tenure, DAs must depend on influential interest groups to prevent their ouster, even if the human cost is far more grave.

While a politico who concerns himself with neighborhood character may be satisfied with his success in promoting inefficient land-use, one who concerns himself with criminal justice is likely to only be content when as many suspected criminals are imprisoned for as long as law allows. DAs therefore have strong incentive to push for harsh sentences, even when they might be inappropriate. The accusation that a DA is ‘soft on crime’ is a death sentence, even in progressive bastions like San Francisco, as former DA Chesa Boudin’s successful recall demonstrates. Given these egregiously warped incentives, it is unsurprising that no other nation on Earth directly elects their criminal prosecutors. Rather, most countries appoint national bodies to deal with prosecution, who in turn delegate responsibility to local teams so as to not overwhelm the capital office. Therefore, California should follow suit. The state should fire all current elected DAs and appoint new ones recommended by an independent, technocratic body of legal professionals. Doing so would do more to advance the rights of the accused, and decrease the rate of excessive punishments than any single ‘progressive prosecutor’ could hope to achieve in a lifetime.

Photo of Chesa Boudin, former District Attorney of San Francisco, taken by Jim Wilson/The New York Times

City councils and District Attorneys may suffer from being the acute focus of highly organized zealots, but this limelight sets them apart from the bulk of local electeds. If these officials bear an excess of attention, the overwhelming majority of their associates – auditors, city treasurers, school board members, and the like – languish in the shadows of anonymity. The question of who should fill these low-profile, often highly technical roles is given little thought by voters; what masochist would subject themselves to a TV debate on municipal accounting practices? As a consequence, the biggest barrier to a hopeful’s dream of becoming a local official is the filing fee.

School boards are tasked with overseeing one the most important functions of government yet are frequently composed of a grab bag of personalities. The president of the Sacramento school district, for instance, has no formal experience in pedagogy. Rather she spent the majority of her career as a legislative assistant for the California District Attorneys Association. The lack of professional expertise in these positions does more than create amusing resumes for those involved, its leads to empirically worse governance. Alexander Whalley, an economist at the University of Calgary, analyzed the performance of appointed city treasurers against elected treasurers and found the former were associated with borrowing costs 13 to 23% lower than their elected counterparts.

A forceful injection of competence is sorely needed, but voters cannot realistically be expected to do the job on their own. Thankfully, they do not have to. The State Board of Education and the Department of Finance are both staffed with genuine experts in their respective fields but currently rely on a motley crew of local officials to enact their work. Untold good could be achieved by cutting out the middleman and having policy set and enforced by those most familiar with a subject.

The oft-cited idea that communities can meaningfully regulate themselves has no legs with which to stand. In the best of circumstances local governments represent not the will of the whole of a community, but those mobs of retirees with an ax to grind. They entrench the power of the landed by limiting who may have a say – one can’t vote for a new mayor if one can’t afford to live somewhere. They reward knee-jerk heavy-handedness with regard to law out of principle. They elevate the grossly inept out of willing ignorance. Traditional assumptions about what degree of local control is appropriate rely on the average voter caring about local politics, but the brutal fact of the matter is that 65% of Americans can’t name their own Congressperson, with local knowledge even lower still. I don’t pretend the percentage who can name their state-level representative is much better, but I am willing to bet it’s higher than those who can name their coroner, an elected official in some counties. Until the median voter can name half their Board of Supervisors, it is best to give their powers to the level of government more likely to face public accountability, and to cede all control to the state.

Edited by Cynthia Hoang-Duong