The Herstory of Hurricanes

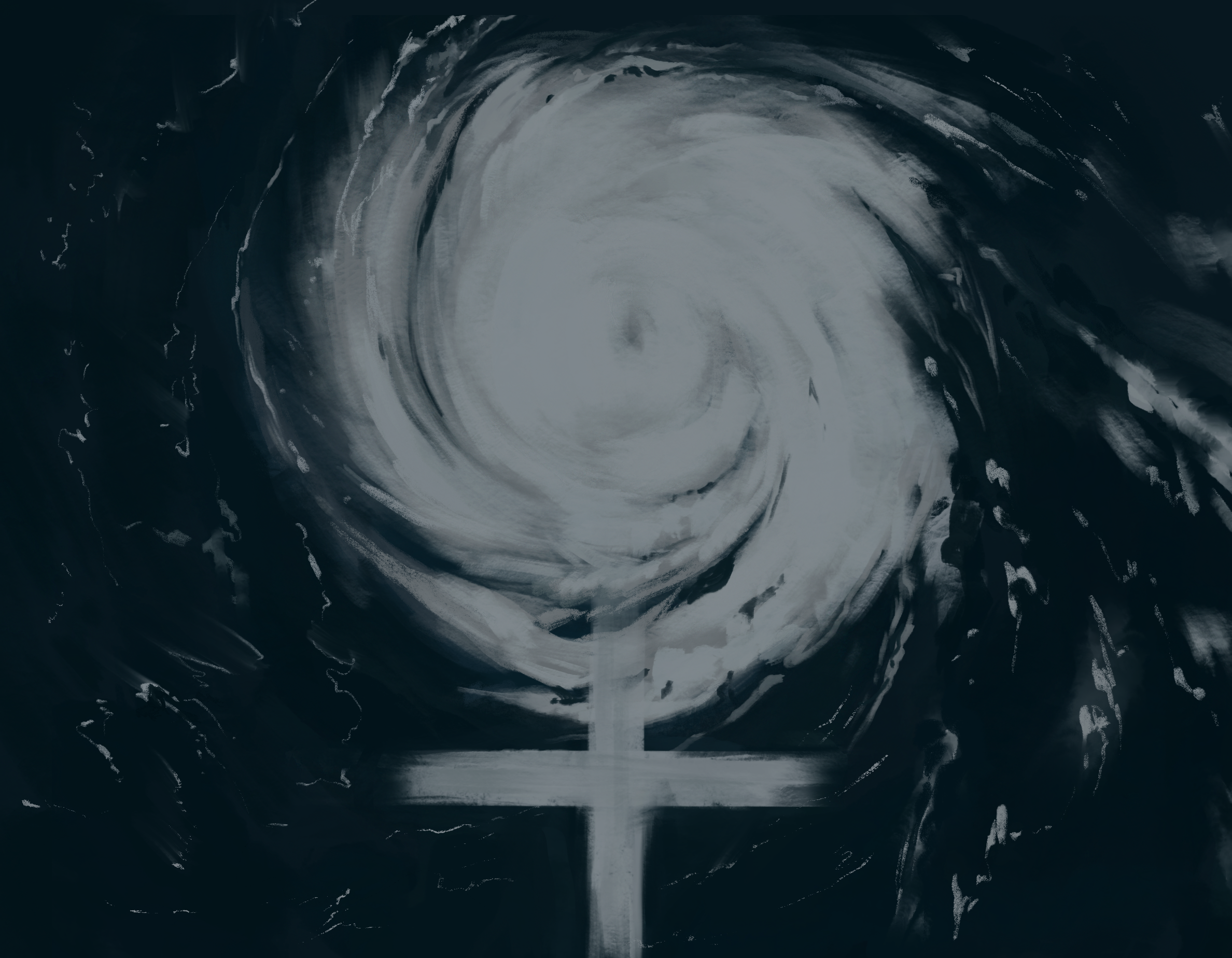

Graphic by Laura Zhang

“Angry woman.”“A neurotic lady, if she could be called a lady.” “The worst-tempered brat.” “[She] shrieked like a woman in labor.” These gendered remarks are real descriptions of what people think of hurricanes. The language used to describe hurricanes and the gendered names associated with storms have caused a recent spark in activism to address the inherent sexual hierarchy prevalent in modern American society. Most recently, with Hurricane Ian, Floridians and residents of other southeast states were urged to prepare as national and local news sources hyperbolized their coverage of the storm. However, this is not always the case, as a topic as impertinent as hurricanes can serve as a beacon of the deeply rooted gender hierarchy plaguing American society.

The long association between women’s behavior and natural disasters arises from the World War II era and the publication of a maritime-themed novel. In 1941, a then-University of California, Berkeley, professor, George R. Stewart, released a renowned novel titled Storm, in which all the characters in the story are left nameless except the tropical storm, Maria. Shortly after this book was released, people throughout the United States adopted the practice of naming storms and tropical weather. The practice was quickly skewed to reflect the sexism prevalent at the time. In order to protect valuable information on storms occurring in the US and other locations from being intercepted by Axis powers, soldiers began unofficially naming the tropical disturbances after their wives and girlfriends, forming a new code.

Soon after the practice was sparked, the rest of the nation followed suit. This was the catalyst of the long tradition of comparing women’s behavioral attributes to the terror and destruction of storms.

As women-named storms flooded the country, people began to lean into the gendering and personification of weather, employing the sexist association to bolster inequality. Weather reporters, media outlets, and just about every other person who talked about incoming storms, with or without intending to, gave the storm traditionally feminine behavior. Reporters spoke of storms “flirting” and “teasing” the coast, gave hurricanes an “unpredictable” nature, and even used the gendered language of “penetration” when discussing hurricanes. This association between women and hurricanes also gave men in power the opportunity to poke fun at the stereotype that women are emotional. As storms were being downgraded from a “tropical storm” to a “tropical depression”, the media wasted no time making jokes about the storm and “her feelings.”

The use of women's names for extreme weather, originally brought about in the midst of the second World War, is a symbolic remnant of the rampant sexism cemented in American society. During the war, women were finally allowed to enter the labor force with men away overseas, freed from their prior imprisonment in the domestic sphere. As the war came to a close, men fighting across the pond returned home and expected women to fall back into their domestic roles. But, having tasted equality, they refused to be contained in the home once again without a fight.

One woman, Roxcy Bolton, took this into her own hands, fighting against the blatant sexism behind the naming of storms. Bolton was an influential Floridian feminist who helped victims of rape by providing them a space for recovery. Bolton spent a large portion of her time working with the National Weather Bureau and demanded that they change the criteria behind the naming of storms to reflect respect and gender equality. In her fight, she even went so far as to tell the Bureau to change the name from “hurricane to himicane” and begin naming hurricanes after Senators since “they delight in having things named after them.” Bolton and other feminists in the late 1960s kept this fight going for years until 1979, when the National Weather Bureau and the World Meteorological Association finally agreed to switch the naming of hurricanes to include male and female names equally.

Despite having eroded the sexism in hurricane names, the public’s perception of women-named storms in the decades following reflect just how deep-rooted the gender hierarchy is in today’s society. Female storms continue to be viewed as less dangerous and less impactful due to their association with female inferiority. Female-named storms are perceived as “weak” and “frail” illustrating the sexist norms of female inferiority and weakness.

This phenomenon was clearly seen with the arrival of Hurricane Eunice. As the storm approached landfall, Twitter flooded with sexist comments comparing Hurricane Eunice to an older woman. Users claimed Eunice made them “think of a kindly old lady” and such a commonly female name “does not make me fearful or aware.” Others took to social media exclaiming that Hurricane Eunice was experiencing “menopause” and that if the public were expected to be afraid, the storms should be named something more intimidating.

Because people view feminine storms as less dangerous and ignorable, they fail to adequately prepare for the reality of the storm's power. As the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explains, “Feminine-named hurricanes (vs masculine-named hurricanes) cause significantly more deaths, apparently because they lead to lower perceived risk and consequently less preparedness….” This means that female storms end up being more fatal and causing more injuries than male storms due to the sexist mindset that believes female storms to be weaker and more frail than male storms. Studies have even shown that “changing a severe hurricane’s name from Charley to Eloise could nearly triple its death toll,” illustrating just how detrimental implicit sexism can be.

Studies about this phenomenon have also shown that when subjects are asked about identical storms with the same category rating, they were more likely to evacuate and take precautionary measures for storms that were named after males compared to storms named after females. One study asked participants to rank how likely they would be to evacuate for a storm based on the name of the storm and the category level. When asked about two identical storms with the only difference being the gender of the name, the study produced a clear difference in the participants' responses. Participants were more likely to evacuate for a storm named “Christopher” than an identical storm named “Christina” and would prepare for a storm named “Alexander” but ignore a storm named “Alexandria”. This implicit sexism suggests that the deeply rooted gender hierarchy and sexist language used in everyday life, especially in American society, has real and lasting detrimental effects on the health and wellness of the nation, while also keeping gender progress stagnant.

Gendered language and gender inequality have become such an ingrained part of American culture that something as trivial as the naming of hurricanes has become a subtle vector of the sexism that is still so prevalent in modern society. This lasting idea of female inferiority has leaked its way into nearly every aspect of American life, leaving the battle of activists, like Bolton, unfinished.

There are different routes that can be taken now in order to remedy this long-lasting sexism associated with hurricanes. The first, and most obvious, being returning to the phonetic alphabet naming system. Originally, the names of storms were to be modeled after the words associated with each letter in the phonetic alphabet. This plan stuck around for just two years, until a new international phonetic alphabet was adopted. However, the National Weather Bureau could return to this method of naming, as the phonetic alphabet is solidified and offers a gender-neutral method of naming storms. Another path to solving this gendered issue would be to use famously gender-neutral names. The names used to identify hurricanes do not have any specific regulations or requirements to meet, but rather are chosen seemingly at random by the National Weather Bureau. Instead of relying so heavily on clearly gendered names and allowing the implicit sexism in society to leak into the process, the Bureau can simply choose to only include names that have been used historically for both male and females. This will provide a long list to choose from: Tyler, Charlie, Quinn, Alex, and the more modern non-binary names such as Arrow and Rebel. Lastly, climate activists and feminists alike have also provided a comical proposal for a new naming process. Bill McKibben, an American environmental activist, offered the idea of naming hurricanes after the big fossil fuels companies that have created the environmental conditions for the storms. He offers the ideas of Hurricane Exxon or Hurricane Shell. Other environmentalists even go as far to include the US Secretary of State and the leader of the Environmental Protection Agency, as Hurricane Rex Tillerson or Hurricane Scott Pruitt.

However, there is still the lasting belief that, even if one of these alternative methods for naming hurricanes is selected, it will not erase the enduring gendered perceptions of storms. The issues of hurricane naming displays how the remnants of the gender hierarchy within American society have seeped into different and seemingly trivial aspects of life. At the same time, it also illustrates the need to address the deep-seeded issue of gender inequality that is still plaguing society and continuing to fight for changes. Feminists, like Bolton, have begun this battle to create a just society, but it is our challenge now to continue the fight for equality.

Edited by Jonathan Sunkari