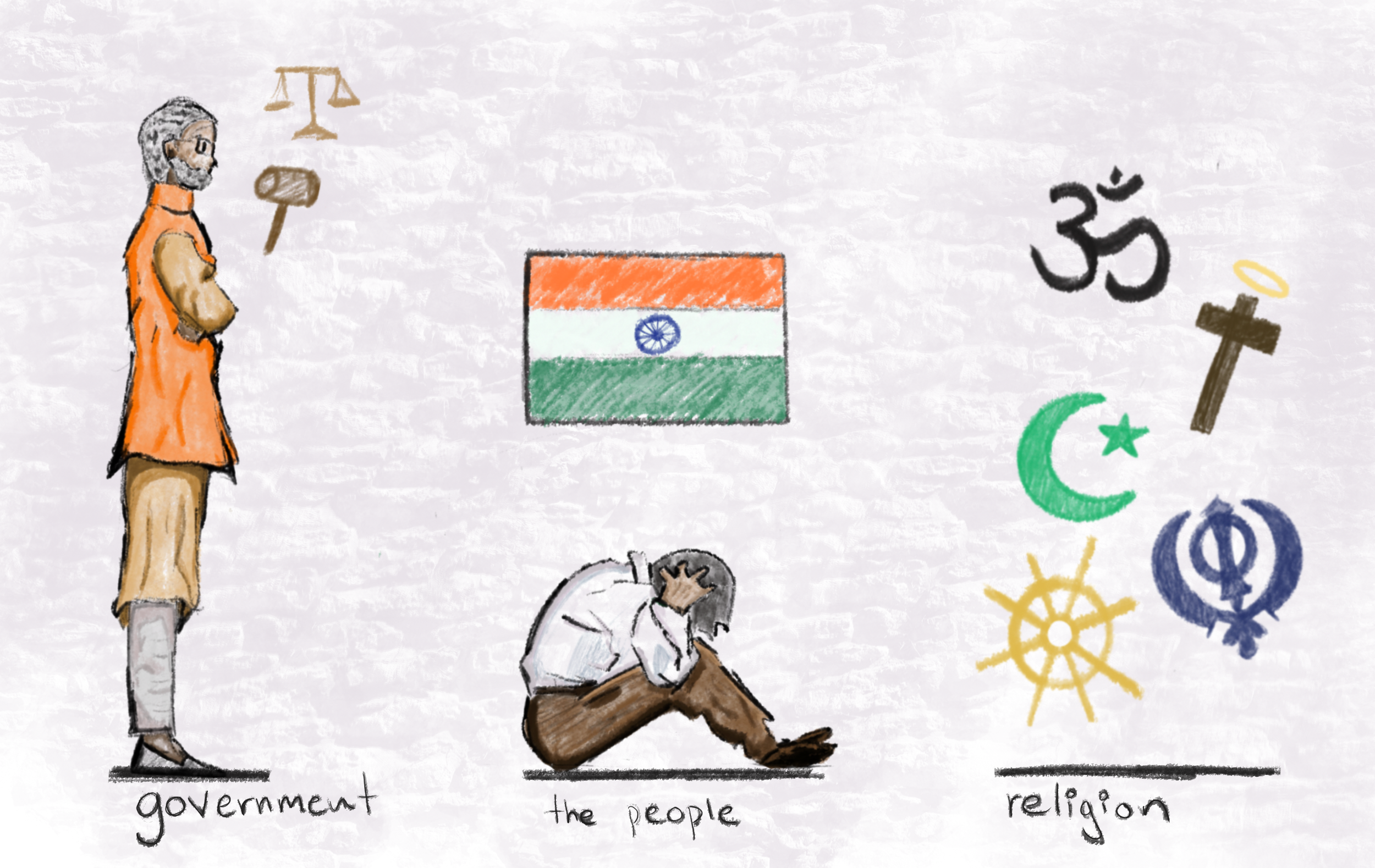

The Struggle Between Secularism and Majoritarian Politics over India's Personal Legal System

Art made by Gil Evangelista Martinez

In recent years, the government of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Prime Minister Narendra Modi has attracted criticism from internal and international actors alike for its majoritarian policies. These include the repeal of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution providing autonomy to the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir along with the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). The CAA expands the provision of citizenship for refugees from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh exclusively to non-Muslim minorities, while the implementation of the NRC in the state of Assam may disproportionately target Muslim citizens through its efforts to identify and deport illegal immigrants. Clearly, at least from the perspective of Western media outlets like the New York Times, the Bharatiya Janata Party has engaged in an assault on the secular principles of the Republic of India.

“Many among India’s liberal intelligentsia see Mr. Modi as a threat to India’s secularism, which is enshrined in its Constitution. It is a characteristic that distinguishes India from Pakistan and binds a nation of extraordinary diversity.”

The Workings of Indian-Style Secularism

In the Western world and especially in the United States, secularism is defined as the “separation between religion and state.” However, in many countries, such a separation does not exist in its entirety. To truly understand secularism, the term must be disaggregated into two social components: “Laicism” and “Accodomationism.” Laicism is a direct translation of the French term for secularism, laïcité, and insists on a rigid separation between the role of religion in public and private life. Meanwhile, accommodationism does not completely restrict religion from public life but places all faiths on an equal footing–preventing one from holding a dominant position. Only in the laicist model is there a highly strict estrangement between religious affairs that extends into schools, universities, and public places. The United States is a prime example of a country that practices accommodationism, considering its constitution only prohibits the “establishment” of one religion over all others.

While India also follows an accommodationist model, it is important to identify the intricacies of how secularism functions in this prominent democracy. Following independence, India’s leaders deemed a secular regime to be the most appropriate to govern a country of incredible diversity. However, criticism of this system often arises due to its unequal treatment of individual citizens. In the late 1970s, a civil suit by a Muslim woman, Shah Bano, involved her right to alimony from a previous marriage. The Supreme Court of India ruled in Bano’s favor in 1985, while members of the Indian Muslim community and the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board opposed the verdict. A year later, the ruling-Indian National Congress later passed a piece of legislation that diluted the scope of the verdict to align more closely with Muslim Personal Law. In turn, the Supreme Court upheld their previous verdict and nullified the law.

In the Indian Constitution, there is a provision calling for a “uniform civil code,” that would apply to all religious groups. However, in practice, each major religion possesses its own set of laws that govern personal matters (divorce, inheritance, succession). Muslims have the option of using their own personal law courts that utilize a form of “Anglo-Mohammedan” law that derives itself from Shari’a and statutes derived from British civil law. In particular, the Shah Bano case brought forth the glaring disparities between the sets of laws that may apply to an Indian citizen. Although the Government of India has rarely involved itself in Muslim personal law with the notable exception of the 1986 Shah Bano case and the abolition of triple talaq, it has comprehensively reformed civil laws governing Indian Hindus, through legislation such as the Hindu Marriage Act (1955), Hindu Succession Act (1956), Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (1956), and Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (1956). As a result, the Constitution of India prioritizes the community-based autonomy of minority groups over equality between individuals, which is often misconstrued as “minority appeasement.” In today’s politics, the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party labels the enactment of a uniform civil code as one of its most prominent policy goals.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was originally founded as the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) by lawyer and barrister, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, in 1951. Mukherjee was previously a leader of the Hindu Mahasabha, a right-wing organization that based its ideology on Hindu unity, political mobilization, and the concept of a Hindu rashtra (state). Following the assassination of M.K Gandhi by prominent Mahasabha member, Nathuram Godse, the tide turned against the religious right in India. In this context, Mukherjee broke away from the Mahasabha to form the BJS in 1951. The Jana Sangh noticeably toned down the Mahasabha’s rhetoric in its early years and adopted policies revolving around nation-building and assimilating India’s religious minorities. With regard to the Uniform Civil Code today, the BJP still claims that their sole agenda is to ensure that the laws of the land treat citizens equally and that individuals of different communities should be just as “Indian” as everybody else. However, such rhetoric is perceived by many members of the Muslim community as an affront to their autonomy and individuality as a separate religious group. Pew Research surveys show that Indian Muslims are just as patriotic as other religious groups. However, a majority also supports the retention of separate legal codes for Indian Muslim citizens, though a plurality is in favor of the government curtailing certain unequal religious practices such as triple talaq.

Ultimately, it is important to examine the distinct nature of Indian secularism, as the concept of a Uniform Civil Code that the BJP envisions, does not seem especially different from French laicism. However, since the party possesses a history of stirring up feelings of communal unrest among India’s population, their argument about a uniform civil code must be viewed with a certain degree of skepticism. The party commonly uses terms such as “pseudo-secularism” and “minority appeasement,” to undermine the credibility of India’s current legal framework. It must be understood that secularism and accommodationism are different altogether; the latter has existed in India’s polity for millennia.

"The beloved of the gods, King Piyadasi, honors both ascetics and the householders of all religions, and he honors them with gifts and honors of various kinds. Whoever praises his religion, due to excessive devotion, and condemns others with the thought ‘Let me glorify my religion,’ only harms his religion. Therefore contact between religions is good. One should listen to and respect the doctrines professed by others. The beloved of the gods, King Piyadasi, desires that all should be well-learned in the good doctrines of other religions."

-12th Edict of Emperor Ashoka (304-232 B.C.E)

In terms of proper separation between religion and state, this has never existed in India. The Indian government regularly involves itself in religious affairs through donations and endowments to religious schools, organizations, and houses of worship. Thus, the Constitution of India was constructed around the premise that Indians are fundamentally religious people, rather than insisting on the opposite. In the 1960s, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri best summed up the nature of Indian secularism.

“While I am a Hindu, Mir Mushtaq who is presiding over this meeting is a Muslim. Mr. Frank Anthony who has addressed you is a Christian. There are also Sikhs and Parsis here. The unique thing about our country is that we have Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Parsis, and people of all other religions. We have temples and mosques, gurdwaras, and churches. But we do not bring all this into politics. This is the difference between India and Pakistan. Whereas Pakistan proclaims herself to be an Islamic State and uses religion as a political factor, we Indians have the freedom to follow whatever religion we may choose, and worship in any way we please. So far as politics is concerned, each of us is as much an Indian as the other.”

-Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, 1965

Although the concept of a uniform civil code was indeed written into the Indian Constitution, it cannot be enacted by a majoritarian government that polarizes the nation for votes. The framers of the Constitution were correct in perceiving the necessity of a single legal code for the entire nation–but as a source of national unity rather than exclusion. Secularism in India broadly means that religion does not inform political decisions, but also permits the state to involve itself in religious affairs and dispense money to religious institutions. The collection of state funds to maintain a religious site is not a violation of this principle. Instead, the largest threats to the pluralistic nature of Indian society are political parties that use religion as a tool to “divide and conquer.”