The First Amendment, Copyright, and Warhol

Graphic made by Richard Pham

When expressing an idea or creating content, creators consciously and subconsciously reference artistic works and concepts that they’re familiar with due to our unavoidable encounters with creative content. Literary works run rampant with references to their predecessors, many classical artists were trained by mimicking their master’s work, political speeches often quote influential figures, and musicians often sample other popular songs. Free speech and expression in the modern era is innately referential. However, as of Oct. 2022, this referential nature is being put on trial in the case of Warhol v. Goldsmith; a copyright case that has the potential to prevent new creators from utilizing older works.

Original Photo by Lynn Goldsmith

The case itself seems relatively straightforward. In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith styled and photographed the artist Prince, and her agency licensed the photo to Vanity Fair in 1984 so it could be used as a reference by the artist Andy Warhol, though Goldsmith was unaware of who the artist was for an upcoming article. In the following years, Warhol created fifteen other works based on Goldsmith’s photo, without her knowledge. Goldsmith herself remained unaware of the Prince Series until 2016 when it was showcased in a Vanity Fair article celebrating Prince’s life.

The picture of Prince on left and the Andy Warhol artwork created by its “inspiration.” Graphic made by Richard Pham

After finding out about the Prince Series, Goldsmith then informed the Andy Warhol Foundation that she believed the series was an infringement of her work under copyright law and registered the original photo as an unpublished work with the U.S. Copyright Office. Soon after the Andy Warhol Foundation sued Goldsmith, claiming that the series was fair use, and Goldsmith issued a counter-suit, claiming that the series was in fact copyright infringement.

The U.S. Second Circuit Court ruled in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation. They ruled that the Prince Series was actually transformative as it held a different character, showing Prince as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure” rather than the “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” seen in Goldsmith’s photo, and included a variety of artistic choices which transformed the original Goldsmith photo. The Court also stated that the Prince Series was recognizable as a “Warhol” and not a realistic photo of Prince as depicted in the original.

However, Goldsmith appealed the case to the Second District Court of Appeals, and in 2021 Judge Gerard E. Lynch issued one of the most controversial rulings in copyright history. Ruling in favor of Goldsmith, the court stated that the Prince Series was in fact not transformative, as it “retain[ed] the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.” In a notable paragraph, Judge Lynch noted that the Prince series is closer to a derivative work than a transformative work, yet still is not necessarily a derivative work. This ruling places far more scrutiny on the recognizability of the source material in the new work than any law or court decision ever has.

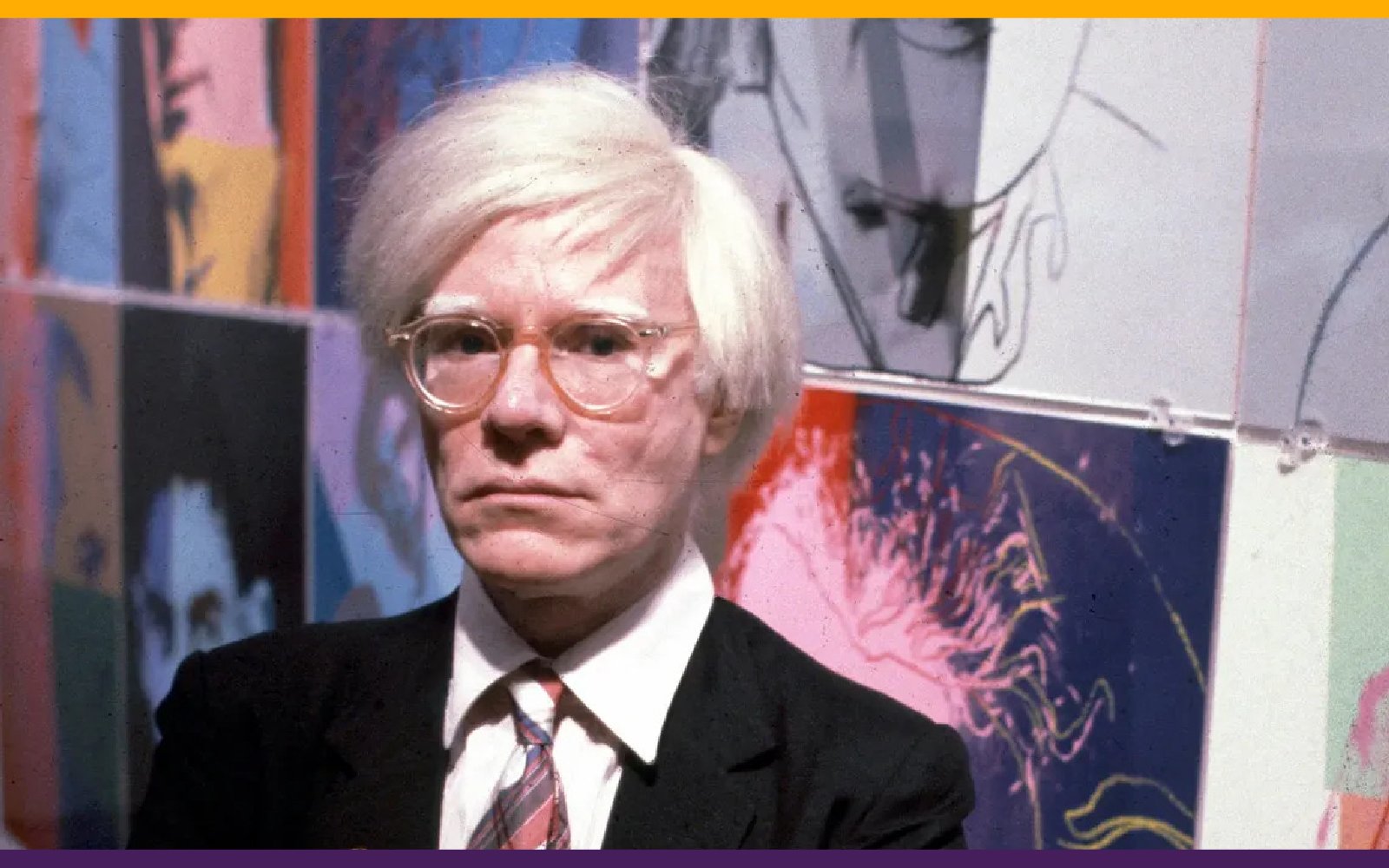

Image of Andy Warhol, edited by Richard Pham

This decision has been widely derided by artists and First Amendment advocates. As it both defies and warps past precedent in a way that has the potential to completely change the way copyright functions as a whole, and not just for traditional artistic works, but for political satire as well. If one were to apply the precedents of Google or a wide variety of other cases like Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music (which held that a parody of a song was fair use), it would be plain to see that the Prince series was fair use.

The question before the Supreme Court is whether or not to uphold this decision by the Second District Court of Appeals; which would limit the creative liberties of creators and place even tighter restrictions on the use of copyrighted material. It is a decision that completely flies in the face of current copyright laws and American jurisprudence and presents a threat to creative industries, as well as protections under the First Amendment. However, to understand the threat presented by Warhol v. Goldsmith, we must understand the complex landscape of copyright law and its connection to the First Amendment.

The connection between the past works and the creation of new works that copyright seems to be on every creator’s mind. When a Youtuber posts a political video essay, they have to wonder if their five-second use of a Star-Spangled Banner recording will cause their video to lose monetization, or worse become suppressed entirely. Stephen King had to request the use of lyrics for his novel Christine, otherwise, he would have likely been sued for copyright infringement for daring to quote “take you for a ride in my car-car.”

Seen in this light, it is clear that copyright inherently places a restriction on free speech. Current copyright law prohibits a person from publishing someone else’s book without their permission and copying their music or art without consent. Your speech is not protected if it was originally someone else’s.

But this does not mean that copyright laws as a whole are unconstitutional. Copyright laws represent a great restriction on the First Amendment while simultaneously encouraging free speech more than any other piece of legislation. The Constitution outright calls for copyright laws in Article One, Section Eight, stating that Congress can create laws to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” By enabling creators exclusive rights over their works for a set period of time, copyright laws actively encourage creators to publish new and original works, as they will (in theory) be the sole beneficiary of its sales. These new and original works contribute to public discourse and further encourage the propagation of new ideas.

Copyright laws have changed over the years, namely in expanding the amount of time the author has exclusive rights over the work to their lifetime plus 70 years. The original Copyright Act of 1790 was quite limited in its protections, granting creators only 14 years of exclusive copyright, and allowing them to renew for an additional 14 years. However, changes by the Supreme Court and subsequent revisions of the 1790 Copyright Act, have broadened the public’s ability to use copyrighted works.

One important change to copyright law made by the Supreme Court is the idea/expression delineation, outlined in the 1879 case, Baker v. Selden. This delineation holds that while a work’s expression may be protected by copyright, the ideas behind it may not be. Someone may make a movie about some talking vegetables, with the overarching theme being that true justice comes from community-based action and taking into account the context of acts committed. While you cannot make the exact same movie about those talking veggies, you can create works that comment on and expand upon the ideas made within the movie.

In 1978, Congress passed the Copyright Act of 1976, a major piece of legislation that was made with the goal of clarifying what constitutes copyright infringement on an original work. This act revised the original Copyright Act (something which hadn’t been done since 1909), namely with the goal of updating copyright law to keep track of rapidly advancing technology, such as the internet. Most notably, Section 107 outlined the “fair use doctrine,” which analyzes work on account of four factors: the purpose/character of the new work (i.e. is it transformative, does it create new meaning or expression?, is it commercial or non-profit), the nature of the copyrighted/original work (is it published or used for educational purposes?), how much was taken from the original work, and whether the new work harms the market for the original. These bounds are subjective and flexible and aim to balance the ownership rights of creators with free speech rights, making fair use crucial to free expression and American culture. However, the case of Warhol is likely to place unprecedented restrictions on the fair use doctrine, which the Court has historically protected.

Fair use case law has generally ruled in favor of the new creator and has become more encompassing through Supreme Court rulings. Many legal academics state that this is because fair use is one of the few copyright protections available to creators at all and that it is also ineffective in protecting small creators who cannot afford to litigate. In 2011, a copyright infringement for damages less than $1 million cost $350,000. Those who can litigate, and whose work is found to be fair use or transformative have an average win rate of 90%. To be transformative, a work needs to add new meanings, insights, or commentary to the original work. For example, using a clip of a John Wayne movie in a video collage that discusses the idea of the “wild west” as it relates to colonialism, would be transformative.

The recent case of Google Llc V. Oracle America, Inc. showcases directly the ambiguity and expansion of fair use best. In order to make it easier for programmers to do their jobs and not need to learn a new coding language, Google took 11,000 lines of code directly from Java, which was owned by Oracle. SCOTUS ruled in favor of Google, claiming that this copying (which was undisputed) was not copyright infringement, as it was transformative and only copied a small portion of Java coding. Its transformativity stemmed from the code’s new use.

Given the history of fair use, it is clear to see that the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has made an erroneous judgment which flies in the face of past precedent. Not only does it disregard the history of fair use, copyright infringement, and transformativity, but it also presents a threat to the artistic community and the right to free speech, particularly when it comes to political satire.

The line of reasoning presented by the Second Circuit of Appeals holds a strong similarity to those utilized by George W. Bush Jr.’s presidential campaign to repress critical speech. In 1999, Zach Exley, created the website, gwbush.com, which was modeled after the then Texas Governor, George Bush Jr.’s presidential campaign website and included “satirical stories about Mr. Bush”. The website, which is still up, features George Bush picking his nose, fake audio advertisements, and a picture of George Bush with the word “Crackhead” flashing over it.

Soon after publishing the website, the Bush campaign sent Exley a letter claiming that the website was copyright infringement and threatened to sue if Exley did not remove the material he used from the official campaign website. In this instance, it is clear that the Bush campaign did not wish to protect their intellectual property or maintain their exclusive rights over campaign slogans or website design. The goal was to silence the political satire which criticized George W. Bush.

While the threat was unsuccessful at the time, viewing this case through the lens of the Second Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision presents a daunting image. For example, if the Nancy Pelosi campaign posted a video where the Speaker appeared to be dozing off and someone decided to GIF that section to mock a “sleepy Pelosi” and claim that she is an ineffective leader who should be ousted, would that be protected under fair use? Likely not, as it would still technically maintain the essential elements of that clip, with no significant alterations.

Upholding the Second Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision in the Warhol v. Goldsmith case threatens political satire such as Exley’s, as it enables public officials to pursue litigation against creators. Creators who likely lack the immense legal resources that a public official would have at their disposal and who create unfavorable works utilizing media that has been copyrighted by the official. This also applies to organizations favorable to public figures and that publish media about them, like partisan organizations or issue-based organizations, like the Justice Democrats. They can sue for copyright infringement against those who are not acting according to their interests and have a solid case. This presents an inherent threat to free speech, as it allows for political speech to be suppressed by the newly expansive copyright regime.

This threat is right on the horizon, as it appears that the Justices are leaning toward ruling in favor of Goldsmith. In oral arguments on October 12, 2022, the Justices seemed to be both confused and opinionated. What appears to be most auspicious, however, is the Court’s reading of the first fair use factor, also known as the transformativity factor. Instead of focusing on the different artistic uses and ideas communicated, as is more traditional in artistic cases, the Justices such as Justice Sotomayor and Jackson focused heavily on the commercial natures of the works. This turns the first factor argument into a question of whether the new work was either commercial or nonprofit, while the case question presented to the lower courts was the opposite: questioning if the changes made by Warhol were transformative. These arguments indicate that the Court may introduce a far more narrow reading of the first factor, limiting it merely to a change in the commercial/non-profit nature of the works. That alone presents a major threat to free speech, art, and the production of culture as a whole.

Justice Barrett especially seems to be doubtful of the Andy Warhol Foundation, the legal precedent), and the notion of transformativity as a whole. Barrett claims that it puts too much emphasis on factor four, which asks whether or not the new work harms the market for the original.

As well, the Court seems to doubt their ability to rule on whether or not they have the ability to decide if a new work comments on the original work or merely copies it. Chief Justice Roberts, seeming sympathetic to the Andy Warhol Foundation, expresses his doubt by claiming that while they may not see any major commentary, to art critics it could be revolutionary.

Copyright law is far more encroaching than commonly thought. It impacts everyone’s lives, and such drastic and restrictive changes such as the Second Circuit Court of Appeal’s ruling is frankly dangerous and restricts free expression. It only takes one case, and one Judge writing the Court’s decision to flip decades of precedent on its head and undermine the peoples’ rights. If the Supreme Court had not decided to hear this case and potentially overturn it, this would be the legal precedent used within the Second Circuit, effectively creating a different set of fair use rules in the region.

The Supreme Court now has the opportunity to protect fair use and creative liberties, to usher in a new era of artistic protections. It does not look like they will take it. Instead, it appears that we may be likely to see one of the greatest limitations on free speech and expression in the modern era, ushered in by unelected officials who are about to overrule decades of their own precedent. This will leave a gaping hole in the field of copyright law, further allowing copyright owners to pursue aggressive copyright lawsuits against those who do not act in their favor. While it may be hard to view the U.S. Copyright Office as the new Bastille of American democracy, we should be ready to watch it burn.

Edited by Aryan Nooshi