Climate Refugees: A Call for Change

Artwork credit: Monica Curca

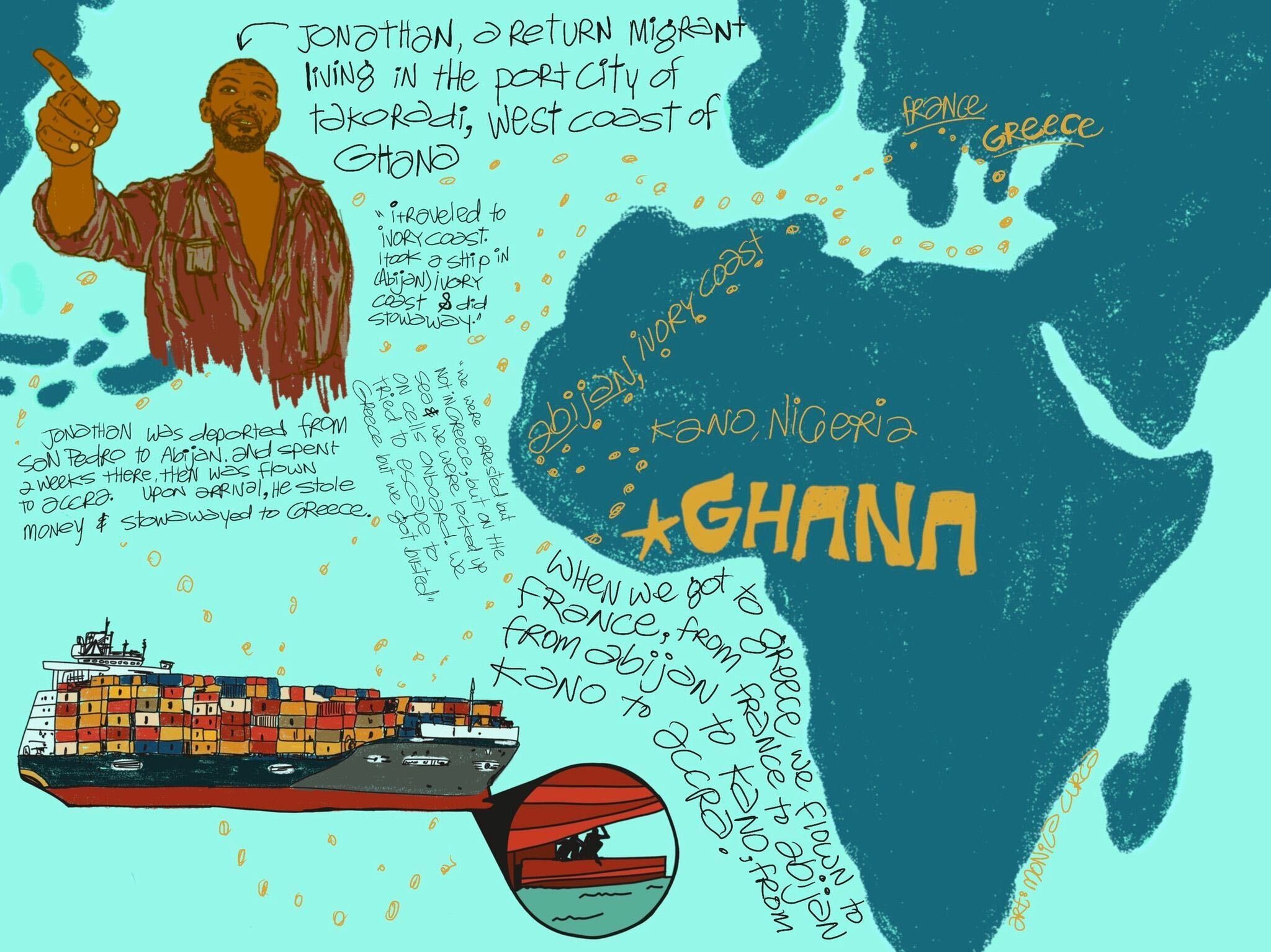

Along the southern coast of Ghana, dozens of young men flock to port cities in hopes of stowing away on departing commercial ships. Two of these men, Jonathan and Michael, are from the port city of Takoradi, whose fishing industry has greatly suffered due to a rapidly changing climate. With severely overfished waters and rising sea levels, Ghana’s coast has become increasingly unfishable, suffering from dangerous tides, perennial storm surges, and dwindling fish populations.

Like other fishermen, Jonathan and Michael decided to emigrate to find new economic opportunities. In Takoradi, Michael faces debt from the costs of his unsuccessful fishing operations and Jonathan is unemployed, foraging for firewood every morning just to buy breakfast. As time has gone on, their prospects of staying have become more and more dire. Their home no longer provides subsistence, and they can’t migrate domestically as their neighbors along the coast have lost their homes and families to tidal waves. In their attempts to stow away, however, both have been caught and deported — Jonathan once, and Michael three times — yet both are still looking to try again.

The changes Ghana is experiencing are not unique. Coastal towns in Bangladesh are being submerged by rising sea levels, agricultural lands in Brazil are turning into deserts, and homes in California face growing risks from floods and wildfire. Our changing climate is displacing people around the world, yet climate migrants — those who leave their homes due to these conditions — face struggles every step of the way. Jonathan and Michael have been unsuccessful in their attempts to emigrate informally, but continue to try because they see no other option. They are climate refugees.

The term “refugee” refers to people who are forcibly displaced from their country of origin based on a well-founded fear of persecution. This persecution falls into four categories regarding race, religion, political opinion, and membership in a particular social group. Because this formal definition does not include those displaced by climate change, though the use of the term is growing, “climate refugees” are not officially recognized under international law, nor are they eligible for refugee status. But when climate conditions force people to flee their homes, on what basis can they leave? To ensure that effective measures are taken to address the displacement they face, climate migrants should be entitled to the same resources and protections as refugees.

What does climate displacement look like?

While many think of dramatic natural disasters as the main contributor to climate displacements, slow-onset ones are a largely overlooked factor. This includes rising sea levels, long-term drought, increasing temperatures, changes in biodiversity, and many other adverse effects. Rather than being demolished in a hurricane, towns and villages can experience recurring damage from annual floods or gradually become submerged by rising sea levels. The difference is that many of these slow-onset events go unrecognized because they are much harder to pinpoint and record. A striking example of this was the Horn of Africa drought in 2022, which resulted in 2.4 million displacements and 534,000 migrations over the span of a year. As of now, climate disasters displace an average of 21.5 million people annually, and by 2050, 1.2 billion are projected to be displaced worldwide.

Beyond initial displacement, the effects of climate change are intertwined with the political and economic factors of everyday life. In many cases, climate change acts as a threat multiplier, exacerbating the impact of other factors that contribute to displacement. Take water contamination, for example. The spread of disease and crop failure is more severe in spaces without the proper infrastructure. Beyond detriments to people’s physical health, agriculture jobs are at risk as food becomes scarce. In some cases, competition over newly scarce resources leads to social disruption and political instability. The number of those in places at high risk for sea level rise has jumped from 160 to 260 million people over the last three decades. As 90% of this population are from developing countries and small island states, the domino effects of climate disasters reveal the pre-existing inequities of our world. Yet because we fail to recognize these slower-onset factors as serious threats, we minimize the experiences of those displaced.

Are climate migrants protected?

While the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recognizes that climate displacements are a growing issue, it fails to guarantee climate refugees the resources and protections necessary to address the changing conditions they face. So far, we’ve only seen soft law approaches, which create guidelines for countries receiving these migrants that are not legally binding. Among the most significant is the 2018 Global Compact for Migration, an agreement dedicated to guiding states' policies regarding international migration as a whole. Additionally, the Task Force on Displacement, which was created at COP21, has developed recommendations to tackle climate displacement and support new research.

While these programs are undoubtedly steps in the right direction, because soft laws are not enforceable, the UNHCR is not institutionally responsible for their implementation. And considering that climate migrants are poorly defined — “climate refugee” is not even an official term — we see that these programs are not able to reach their full potential.

In contrast, the 1951 Refugee Convention offers refugees official protection under international law. In their new countries, refugees have the right to not be expelled or punished for irregular entry, the right to decent work, housing, education, and freedom of religion, and are granted a pathway to citizenship. While climate migrants may not fit into our traditional view of refugees, it is unjust to deny them basic human rights. This applies to anyone who has been forcefully displaced, whether by persecution or by climate disaster. As the world changes, international law needs to adapt, and so does the term “refugee.” In many cases, one’s political, economic, and environmental conditions are interconnected — who is to say this cannot be a new category?

It’s true that the majority of climate migrants move internally — in 2022, this population reached 32 million — but domestic migrants lack the same protections as international ones. Oftentimes, the cities they migrate to are unequipped to handle the massive influx of arrivals. We’ve especially seen this in the Asia-Pacific region, where climate displacements are not a new issue. Dhaka, Bangladesh, currently receives 2,000 migrants daily. Lacking comprehensive governmental funds for migrants to relocate and cities to handle the influx of refugees, most migrants end up joining Dhaka’s slum population of 4 million. Because domestic migrants are not protected, many move internationally. Climate refugees lack protection no matter the route they choose.

Though not yet official, the term “climate refugee” is changing the way we think about migration, displacement, and our changing climates. It provokes conversation and gets us to think about the experiences of those displaced. We’re headed in the right direction, but the institutional gaps in the protections for climate refugees are why we must continue to challenge existing guidelines and further our pursuit of human rights.