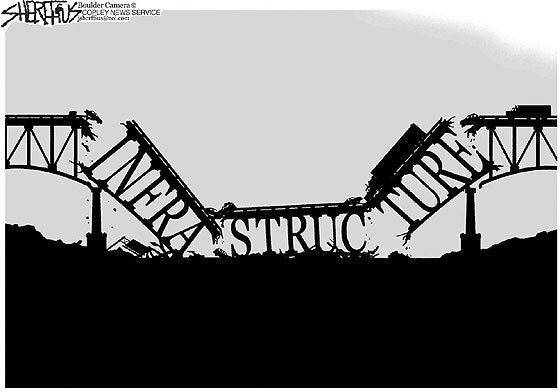

The Basics of Bad Bridges

What you need to know about California's failing infrastructure

“The Basics of Bad Bridges” was originally published in the Berkeley Political Review on March 8, 2015, and authored by Berkeley Political Review staff writer Leah Daoud.

Within the last few years, Americans have become increasingly aware of the failings of our national infrastructure. According to the 2013 report released by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), infrastructure in the United States has been given a grade of D+, meaning that the nation’s roads and bridges are in poor to fair conditions and mostly below standard, with many elements exhibiting significant deterioration.

This problem is even more glaringly obvious on a statewide level. Although infrastructure in California received a grade of C, there is a high concentration of deficient and even dangerous infrastructure. The report indicates that thirty-four percent of the state’s major roads are in a poor to dangerous condition, and the rising number of potholes and other forms of environmental weathering are only contributing to a rise in car accidents. Additionally, more than 2,700 bridges in California are structurally deficient, meaning that these bridges contain significant defects. Moreover, more than 4,100 bridges are functionally obsolete, meaning that the designs of the bridges are not suitable for their current use. To make matters worse, there are over 380 structurally deficient bridges in the San Francisco Bay Area alone, and this number rises in significance when considering the rising population and traffic density in the Bay.

So far, the government has followed a policy of using federal money to build new bridges, rather than to improve or to replace the old ones. Although there have only been a handful of high-profile bridge collapses in the United States, this “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” policy continues to put millions at risk. Infrastructure in California is clearly fatally flawed and the longer California waits to address this problem, the more likely it is that deadly collapses will become commonplace.

“The whole system is cracking,” says Mark Watts, executive director of Transportation America. “Almost half of the urban areas with the worst road conditions are found in California. Despite our successes in increasing transportation infrastructure investment over the past few years, we are not even close to digging ourselves out of the hole that years of neglect created.”

The task of raising money for the state’s $59 billion in needed transportation upkeep seems inaccessible, even though lawmakers have long been searching for a solution to our infrastructure crisis. Right now, road maintenance is funded by an 18-cent a gallon gas tax that has not been increased since 1994. Collections fell from $2.87 billion in 2003 to $2.62 billion in 2013 and this was caused, in part, by the loss of gas tax revenue from fuel efficient and electric cars. Additionally, tough budget cycles have increased the state’s reliance on debt to finance major projects. Between 1974 and 1999, California issued $38.4 billion in bonds. That figure exploded to $103.2 billion in the past 15 years. Currently, $1 out of every $2 spent on an infrastructure project goes toward paying down the bonds’ interest rather than repairing the actual problem, according to the Department of Finance.

In a recent statement regarding his budget proposal, Governor Brown acknowledged that infrastructure funding has often been neglected. “I have a team working on infrastructure,” he stated, “and we’re going to start engaging the constituency groups, including Republican leaders, and we’re going to try to find out what sources of funding are available to us.”

As admirable as this sounds, Brown’s actual spending proposal tells a different story. His budget allocates $478 million for maintenance of the state’s universities, parks, prisons, and hospitals, a tiny fraction of the needed billions. This hesitancy to address infrastructure head-on is only going to contribute to a cycle of mismanagement. To address the need adequately, the state must either spend more on our bridges and roads or find new sources of funding and this will require more than just a commitment to Brown’s favored project, the high speed bullet train.

In light of budgetary crises around the world, it seems as if public-private partnerships are rising in both popularity and effectiveness. Public-private partnerships, or the construction and upkeep of public-sector infrastructure on the basis of private-enterprise financing, have developed into quite the successful alternative. Projects in Canada, Europe, and Australia have shown that, compared with purely publicly run plans, projects coordinated between the public and private sectors have a better track record of being completed on time and under budget.

In 2006, private companies Cintra Concesiones de Infraestructuras de Transporte and Macquarie Infrastructure Partners were awarded a bid to operate a 157 mile stretch of Indiana’s public roadways. The partnership of private companies paid the state a one-time fee of $3.8 billion for a 75-year agreement to operate the roadway in exchange for the revenue from the tolls. Although investors have not yet seen a return, the project is saving the state an estimated $100 million per year in operating costs and the public-private partnership has taken an enormous burden off the shoulders of local taxpayers.

When it comes to improving its infrastructure, California does seem to be on a bridge to nowhere – but it does not have to be this way. Despite the legitimate budgetary concerns, there is much the state government could do to improve infrastructure and the solution may come in the form of public-private relationships. While public-private partnerships are not necessarily the answer to California’s infrastructure problem, it is certainly time that they be considered. The state’s $59 billion dollar backlog urgently needs to be addressed. Without a renewed focus on strengthening our infrastructure, California could see a rise in bridge and road failures- something the state’s economy certainly cannot afford.